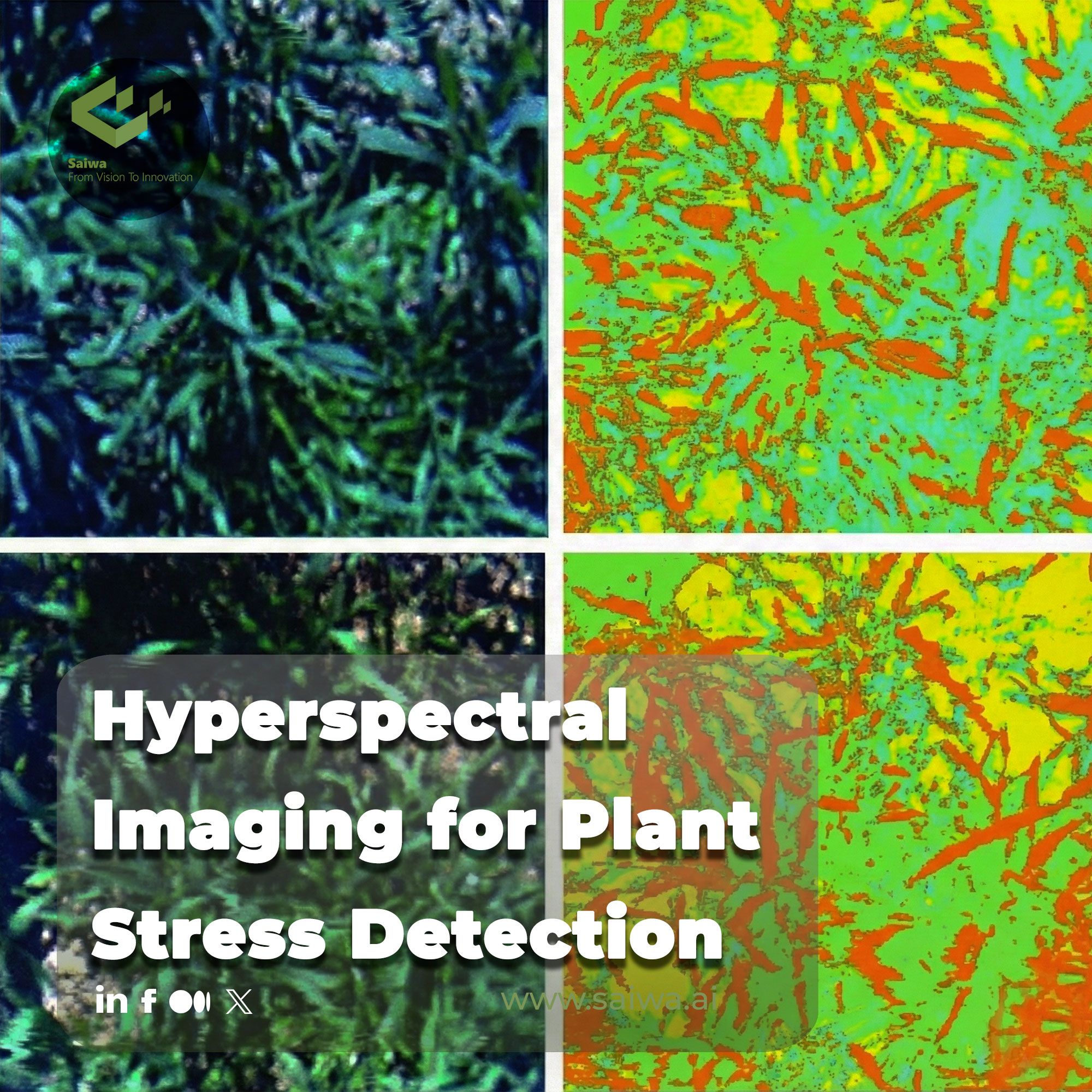

Hyperspectral Imaging for Plant Stress Detection

This article explores the use of hyperspectral imaging (HSI) for early detection of plant stress, covering sensor technologies (UAV, satellite, ground), AI-driven analytics, vegetation indices, and practical workflows from data capture to decision-making. We highlight its advantages over RGB and multispectral imaging, discuss abiotic and biotic stress detection, present real-world applications, and outline future directions for scalable and sustainable agriculture.

What is Hyperspectral Imaging in Agriculture?

Hyperspectral imaging (HSI), or spectroscopic imaging, combines traditional imaging with spectroscopy to capture both spatial and spectral information at the same time. Each pixel records a continuous spectrum, forming a three-dimensional dataset known as a hypercube, which includes two spatial dimensions and one spectral dimension.

In agricultural and environmental applications, HSI typically covers the visible (VIS), near-infrared (NIR), and short-wave infrared (SWIR) regions, generally spanning 0.4–2.5 μm. This spectral range allows for detailed identification of vegetation properties that are not detectable with the human eye or conventional cameras.

From RGB and Multispectral to Hyperspectral (and Why It Matters in 2026)

RGB imaging captures data in just three broad wavelength channels—red, green, and blue—while multispectral imaging samples a limited set of discrete spectral bands. In contrast, hyperspectral imaging collects hundreds of contiguous, narrow spectral bands, providing much higher spectral resolution.

This enhanced spectral detail enables hyperspectral sensors to discern subtle differences in spectral signatures between materials that appear visually similar. In agricultural applications, this capability allows early and more accurate detection of physiological changes in crops, which are often undetectable using RGB or multispectral imagery.

Looking ahead to 2026, this enhanced spectral capability is increasingly critical. Hyperspectral sensors enable early detection of subtle physiological changes in crops, monitoring of soil and water quality, and identification of plant stress or disease that remain invisible in RGB or multispectral imagery. These advancements are driving more precise,>Why Early Stress Detection Changes Farm Economics

Crop stress—caused by factors such as water deficiency, nutrient imbalance, salinity, or disease—has a direct negative impact on productivity. Conventional visual assessment methods often identify stress only after visible symptoms emerge, by which point yield loss may already be substantial.

HSI can detect subtle spectral changes that indicate physiological stress before any visible signs appear. This early detection allows for timely, targeted interventions, reducing yield loss and optimizing resource use, ultimately enhancing both farm profitability and sustainability.

How AI Companies like Saiwa Operationalize Hyperspectral Imaging (UAV, Satellite, Cloud)

Modern AI-driven agritech companies operationalize hyperspectral imaging by integrating advanced sensing platforms (UAVs and satellites) with cloud-native analytics and machine learning workflows. Hyperspectral data collected from hyperspectral sensors mounted on drones or acquired from orbiting satellites are typically transmitted to cloud environments where high‑performance computing infrastructure processes the raw spectral cubes. These systems clean, calibrate, and georeference the data, then apply AI models to extract actionable insights such as crop biochemical traits, stress indicators, nutrient status, and disease signatures.

In practice, companies like Saiwa use UAV-based hyperspectral systems to gather high-resolution spectral data over fields, capturing hundreds of narrow contiguous bands that reveal subtle biophysical changes invisible to conventional sensors. The captured imagery is uploaded to cloud platforms where AI algorithms classify vegetation health, detect anomalies, and generate field‑level analytics that farmers and agronomists can act upon in real time. Similarly, satellite hyperspectral data complement UAV coverage by providing broader spatial context and temporal revisit, enabling longitudinal monitoring across seasons and large landscapes. These multi‑platform workflows empower precision agriculture at scale — optimizing irrigation, fertilization, and crop management decisions while enhancing sustainability.

The Science Behind Plant Stress Detection with Hyperspectral Imaging

HSI is a non‑destructive technique that captures detailed reflectance data across hundreds of narrow and contiguous wavelength bands, producing a spectral “fingerprint” for each pixel in an image. This rich spectral information reflects how plant tissues interact with light through absorption, transmission, and reflection, which are influenced by the underlying biochemical and structural properties of vegetation.

Under stress conditions—such as drought, nutrient deficiency, or disease—the biochemical composition and physiological processes within leaves and canopies change. These alterations affect concentrations of pigments (e.g., chlorophylls and carotenoids), water content, and other metabolites, generating distinct variations in spectral reflectance patterns across specific wavelength ranges. Hyperspectral sensors are sensitive enough to detect these subtle spectral shifts even before visual symptoms appear.

Researchers analyze hyperspectral data using vegetation indices or multivariate analysis techniques such as principal component analysis. These methods quantify spectral differences and allow for the classification of stress levels, effectively distinguishing healthy plants from those under stress. By capturing both spectral and spatial information, HSI provides a comprehensive dataset that supports early detection of plant stress, often before any visible signs develop.

Understanding the Hypercube and Spectral Bands

HSI data are commonly represented as a hypercube, a three-dimensional dataset comprising a stack of two-dimensional images captured at different wavelengths. Each pixel contains a full spectral reflectance profile, enabling precise analysis of plant material at the pixel level.

Modern HSI systems can acquire hundreds of narrow spectral bands, sometimes only a few nanometers wide. This fine spectral resolution provides detailed information that enhances vegetation monitoring and material discrimination.

Spectral Signatures as Biological Fingerprints

A spectral signature describes how a material reflects or absorbs light across wavelengths. Vegetation, soil, and water each display unique spectral patterns due to their specific physical and chemical properties.

In plants, spectral patterns are influenced by leaf pigments, internal tissue structure, and water content. Because these properties change under stress, spectral signatures serve as biological fingerprints, enabling differentiation between healthy and stressed plants.

Red Edge Position and Chlorophyll / Stress Sensitivity

Green vegetation strongly absorbs light in the blue (~450 nm) and red (~670 nm) regions due to chlorophyll, while reflectance increases sharply in the near-infrared (NIR) region. The transition zone between red absorption and NIR reflectance is known as the red edge.

When plants experience stress, chlorophyll content often decreases, leading to higher reflectance in the red wavelengths and shifts in the red edge position. Hyperspectral sensors can detect these changes with high sensitivity, allowing for the early identification of plant stress.

Detecting Abiotic and Biotic Stress with Hyperspectral Imaging

Abiotic Stress: Water, Nutrient, Salinity (with Pre-visual Detection Examples)

Abiotic stresses—including water deficit, nutrient imbalance, and salinity—impact plant physiology and disrupt photosynthetic processes. These stressors modify spectral reflectance, especially in the visible and near-infrared (NIR) regions.

Studies have demonstrated that hyperspectral imaging can detect these stress-induced changes before visible symptoms appear. For example, early water stress in soybean can be identified via shifts in pigment- and water-related spectral patterns several days prior to wilting or discoloration. Similarly, hyperspectral analysis of barley revealed drought responses up to 10 days before conventional indices like NDVI (Normalized Difference Vegetation Index) detected stress. Nutrient deficiencies have also been detected early by observing spectral changes in the visible and NIR regions linked to reduced chlorophyll and altered biochemical composition.

Hyperspectral imaging systems, combined with appropriate data analysis methods such as vegetation indices or machine learning models, enable rapid, pre-visual detection of abiotic stress, supporting timely intervention and improved crop management.

Biotic Stress: Diseases, Pests, Pathogens

Biotic stress, resulting from pathogens, pests, or diseases, leads to measurable changes in plant spectral behavior. Infected plants typically show modifications in pigment content and tissue structure, which are captured in their spectral signatures.

Hyperspectral imaging enables early detection of disease by identifying subtle spectral variations between healthy and affected tissues, often before visual symptoms become noticeable.

When to Use Hyperspectral vs. RGB / Multispectral in the Field

Choosing the right imaging technology for field applications depends on the level of spectral detail required, the objectives of monitoring, and operational constraints. RGB imaging captures only three broad color channels (red, green, and blue), providing basic visual information that is useful for simple tasks such as crop emergence detection or general field observation. However, its limited spectral range restricts its ability to reveal detailed biochemical or physiological changes in vegetation. Hyperspectral and multispectral sensors extend beyond RGB by capturing reflectance in additional wavelengths, enabling more advanced analysis.

Multispectral sensors typically collect data in a few discrete bands (often including near‑infrared), offering improved insight into vegetation health compared to RGB. They are particularly effective for broad vegetation monitoring, biomass estimation, and regular crop health assessment, and because they generate smaller datasets, they support faster processing and real‑time applications in large areas. However, their limited spectral resolution can mask subtle biochemical variations important for early stress detection.

By contrast, hyperspectral imaging captures hundreds of narrow, contiguous spectral bands, creating detailed spectral fingerprints for each pixel. This high spectral resolution enables fine discrimination of crop biochemical and structural properties that are often invisible to RGB or multispectral sensors, making HSI especially valuable for early stress detection, precise nutrient and water status assessment, and detailed material characterization. While hyperspectral data are richer, they also require more advanced processing and computational resources, and the systems are typically more costly and complex to deploy.

In practice, many agricultural monitoring workflows utilize a hybrid approach: RGB and multispectral imaging provide broad, cost‑effective coverage, while hyperspectral data are used where high spectral fidelity and early detection capabilities are critical for decision‑making.

Real-World Applications in Canadian Agriculture

In Canada’s agricultural landscape, hyperspectral imaging is increasingly being applied to address critical plant health challenges on the Prairies and beyond. One notable example is the use of UAV‑mounted hyperspectral sensors to identify clubroot infestations in canola fields. Researchers flew drone missions over commercial canola fields in Alberta and Saskatchewan, detecting small patches of clubroot with high accuracy during the flowering stage—helping farmers map affected areas for site‑specific management. Over 90 % classification accuracy was achieved in distinguishing infected patches from healthy crop using spectral signatures captured by hyperspectral cameras.

Another key application in Canadian production systems relates to Fusarium head blight (FHB) in wheat. Although much research on hyperspectral detection of FHB has been conducted internationally, Canadian grain research and inspection programs have a long history of using visible/NIR hyperspectral imaging to classify Fusarium‑damaged kernels, helping grain quality assessment and food safety evaluation. This work underpins advanced approaches to detecting fungal infections and supporting breeding programs for disease resistance.

Beyond disease detection in canola and cereals, hyperspectral imaging also plays a role in precision agronomy research, such as estimating nutrient status and crop biochemical traits across fields using drone or satellite data integrated with machine learning models developed by Canadian researchers and institutions (e.g., Agriculture and Agri‑Food Canada projects). While frost damage detection via hyperspectral sensing under natural field conditions remains more challenging due to environmental variability, controlled studies show spectral responses to frost stress that could inform future field applications in regions with short growing seasons.

Vegetation Indices vs. AI‑Driven Features

Monitoring plant health in modern agriculture increasingly relies on both traditional vegetation indices and advanced AI-driven spectral features. While indices like NDVI, PRI, and TCARI have long been used to summarize canopy reflectance patterns, they capture only a limited portion of the information contained in high-resolution hyperspectral data. AI-driven methods, by contrast, can extract subtle patterns and interactions across hundreds of spectral bands, enabling earlier and more precise detection of plant stress. This section explores the limitations of conventional indices and highlights how hyperspectral indices and machine learning approaches provide a robust framework for next-generation crop monitoring.

Limits of NDVI, PRI, TCARI for Early Stress

Traditional vegetation indices such as NDVI, PRI (Photochemical Reflectance Index), and TCARI (Transformed Chlorophyll Absorption in Reflectance Index) have long been foundational tools for monitoring crop health. NDVI is widely used due to its simplicity and effectiveness for broad chlorophyll detection, but it primarily captures green biomass and often lags when identifying early physiological stress before visible symptoms appear. PRI and TCARI introduce sensitivity to photosynthetic changes and chlorophyll absorption nuances, yet they remain constrained by the limited spectral bands that conventional multispectral sensors capture. Consequently, these indices can miss early stress signals—such as subtle structural changes or water content variations—that occur outside their targeted spectral combinations, limiting their effectiveness for truly early detection of plant stress.

2025‑Ready Hyperspectral Indices and ML‑Based Indices

Advances in hyperspectral data analysis have given rise to novel vegetation indices optimized for early stress detection. For example, machine‑learning‑driven indices such as MLVI (Machine Learning‑Based Vegetation Index) and H_VSI (Hyperspectral Vegetation Stress Index) leverage data‑driven band selection methods like recursive feature elimination to focus on the most stress-sensitive wavelengths spanning the NIR and SWIR regions. These indices outperform traditional ones by capturing spectral contrasts associated with early physiological changes, enabling detection of stress up to 10–15 days earlier than NDVI in controlled studies. This shift from fixed ratio‑based indices to data‑optimized hyperspectral indices represents a major step toward truly early and robust stress monitoring in precision agriculture.

Combining Indices with ML for Robust Early Detection

An effective strategy integrates traditional and novel vegetation indices with machine learning models to improve early stress detection. Rather than relying only on index values, models such as convolutional neural networks or random forests can analyze these indices alongside raw or processed spectral features to identify patterns linked to early stress. In parallel research, vegetation indices derived from hyperspectral data have been used as discriminative features in classification tasks, revealing that combinations of indices often improve performance compared to any single index alone. While indices like NDVI and PRI provide meaningful baselines, integrating them with ML‑driven features enhances sensitivity to complex stress responses—particularly for early, subtle changes that traditional indices alone may overlook.

Sensors and Platforms (UAV, Satellite, Ground)

Drone/UAV HSI for Field-Scale Diagnostics (Saiwa Drone Services)

Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) equipped with hyperspectral sensors are increasingly used for field‑scale crop diagnostics due to their ability to collect high‑resolution spectral data on demand. UAV‑based hyperspectral imaging delivers fine spatial detail, flexible scheduling, and targeted coverage that is difficult to achieve with satellite platforms alone. This makes UAV HSI particularly valuable for early detection of plant stress, nutrient deficiencies, and disease outbreaks, as well as for monitoring spatial variability across large fields. Recent research emphasizes how UAV platforms excel in capturing crop reflectance patterns sensitive to water and nutrient stress before visible symptoms develop, supporting precision interventions and improved agronomic decisions.

As part of Saiwa’s drone services, we provide consulting sessions on how to integrate hyperspectral systems with advanced calibration routines and custom flight planning to ensure consistent data quality across diverse agricultural environments. Combined with cloud‑based analytics and machine learning models in our Sairone platform, these UAV datasets enable farmers and agronomists to act on high‑fidelity insights at field scale.

Satellite HSI (EnMAP, PRISMA) for Regional Monitoring

Satellite hyperspectral sensors such as EnMAP and PRISMA represent a new generation of space‑borne imaging spectrometers capable of capturing hundreds of narrow spectral bands across visible to shortwave infrared wavelengths. These missions provide synoptic, repeatable coverage that supports large‑area crop monitoring, phenology tracking, and crop classification efforts at regional scales. Compared to traditional multispectral satellites, hyperspectral satellites improve differentiation among crop types and enhance estimation of biophysical parameters, although their medium spatial resolution (e.g., ~30 m) can be a limitation for field‑level precision tasks. Combining satellite hyperspectral data with higher‑resolution UAV or optical imagery can help overcome this trade‑off, creating robust, multi‑scale monitoring frameworks for agricultural landscapes.

These satellite platforms are particularly relevant for large‑scale agricultural decision support, enabling temporal analyses of crop stress trends, land‑use change, and broad phenological indicators that inform policy, insurance, and supply chain planning.

Ground‑Based and Greenhouse Systems for Phenotyping

Ground‑based and greenhouse hyperspectral systems provide close‑range, controlled‑environment measurements that are essential for genetic phenotyping, trait discovery, and early stress detection research. By capturing spectral reflectance under stable lighting and environmental conditions, these platforms reduce noise from atmospheric variability and allow researchers to correlate spectral features directly with plant physiological and biochemical traits. This makes them ideal for breeding trials and controlled‑condition stress assays where precise measurement of subtle spectral changes is critical. Although ground systems do not offer the spatial breadth of UAVs or satellites, they play a central role in calibrating models and validating observations that are later applied to larger scales.

In greenhouse phenotyping applications, hyperspectral imagery is frequently combined with 3D reconstruction and structure analysis to disentangle geometric effects from spectral signals, enabling better characterization of plant architecture and stress responses.

Snapshot vs. Push‑Broom: Which Fits Your Operation?

Hyperspectral sensors differ in how they acquire data, and choosing the right architecture can influence both data quality and operational efficiency. Push‑broom (line scanning) sensors collect spectral information one line at a time as the platform moves, which is typical for UAV and satellite HSI systems and offers high spectral and spatial resolution. Snapshot imaging, by contrast, captures all spatial and spectral data in a single shot, simplifying acquisition and enabling real‑time workflows, albeit often with reduced spectral or spatial resolution compared to push‑broom systems. The choice between these modes depends on project priorities: push‑broom is ideal for detailed mapping and precision analytics, while snapshot systems may be preferred for rapid surveys, automation, or resource‑limited deployments where simplicity and speed are critical.

Practical Workflow: From Data Capture to Decisions

Hyperspectral imaging workflows in agriculture follow a structured process that transforms raw spectral data into actionable decisions. The main steps are as follows:

- Data Acquisition (Flight Planning, Lighting, Calibration)

Careful planning of data collection is critical to cover all the field regions. This involves defining UAV flight paths or satellite revisit schedules, choosing optimal times of day to minimize shadows, and using calibration targets for consistent radiometric measurements. Radiometric calibration ensures that reflectance data are comparable across dates, sensors, and lighting conditions, forming the foundation for reliable analysis. - Pre-processing (Radiometric, Geometric, Orthophoto Generation)

Before analysis, hyperspectral data undergo radiometric correction to standardize sensor response, geometric correction to align images with real-world coordinates, and orthomosaic generation for UAV and airborne data. Additional steps may include segmentation or background removal to focus on vegetation areas, reducing data complexity for downstream analytics. - Cloud and Edge Analytics (Saiwa Cloud Platform, APIs)

Pre-processed data are transmitted to cloud or edge platforms for advanced analysis. Machine learning or deep learning models extract features related to stress indicators, nutrient status, or disease signatures. Scalable cloud infrastructures handle large datasets, model training, and real-time inference via APIs, while edge computing enables near-real-time processing for UAV or ground-based sensors. You can widely use Sairone services in this case. Integration with Farm Management Systems and Existing Workflows

Analytical outputs, such as stress maps or nutrient deficit zones, are integrated into farm management systems (FMS) and existing operational workflows. This enables>Challenges and What’s Next (2025–2030)

Data Volume, Storage, and Processing Bottlenecks

Hyperspectral imaging produces very large and high‑dimensional datasets because of the hundreds of narrow wavelength bands captured for each spatial pixel. Handling these volumes — storing, transmitting, and processing them — remains a major bottleneck for scalable agricultural deployment. Even with cloud infrastructure and modern big‑data frameworks, efficient data management requires advanced compression, distributed storage, and parallel processing (e.g., GPU/TPU systems) to support near‑real‑time inference and long‑term monitoring. This challenge becomes more pronounced when integrating multi‑platform data (UAV, satellite, ground) with varied resolutions and revisit frequencies.

Synthetic Training Data and Generative AI

Building effective AI models for hyperspectral stress detection is constrained by the scarcity of labeled training data that spans diverse crops, environments, and stressors. Large, annotated datasets are difficult and costly to collect in the field, limiting model generalizability. To address this, generative AI techniques — such as GANs and diffusion models — are increasingly being explored to synthesize realistic hyperspectral samples. These synthetic datasets can help augment training sets, improve robustness, and enable models to generalize across conditions. However, ensuring that generated spectra remain physically plausible and representative of real plant responses is an active area of research, and validation frameworks are still evolving.

Building and Standardizing Spectral Libraries

Spectral libraries — collections of reference reflectance signatures for known plant conditions — are essential for many hyperspectral workflows (classification, stress detection, material identification). However, existing libraries are often limited in scope, lacking comprehensive coverage across crop varieties, growth stages, and environmental contexts. Differences in illumination, sensor calibration, and acquisition protocols further complicate cross‑study comparisons. Community‑wide efforts to create open, standardized spectral repositories and consistent metadata practices are needed to improve interoperability, reproducibility, and model transferability across regions and sensor types.

Real‑World Deployment and Environmental Robustness

Despite high accuracy under controlled conditions, many hyperspectral stress detection models lose reliability in real field environments due to variable lighting, atmospheric effects (e.g., aerosols, water vapor), and surface heterogeneity. Spectral signatures that work well in lab tests may degrade under natural sunlight, changing canopy structures, or mixed soil backgrounds, reducing prediction performance. Developing environmentally robust models — with better atmospheric correction, adaptive calibration, and domain‑adaptive learning — is a key frontier for real‑world adoption.

Multi‑Source Data Fusion and Interpretation

Integrating hyperspectral data with other data sources — satellite imagery, weather stations, soil sensors, and IoT networks — is promising for robust stress detection but introduces complexity in data fusion and interpretation. Harmonizing disparate formats, resolutions, and temporal scales requires advanced fusion techniques and careful algorithm design. Moreover, ensuring that models remain interpretable and actionable for agronomists — rather than opaque “black boxes” — will be essential for user trust and adoption.

Cost, Accessibility, and Adoption Barriers

Beyond technical hurdles, economic and practical barriers limit hyperspectral adoption. High sensor and platform costs — especially for UAV/satellite HSI systems — can discourage small and medium farms. Additionally, there is a gap in technical expertise required to operate systems, interpret results, and integrate insights with existing workflows. Education, training, and accessible analytics platforms are needed to bridge this divide and democratize hyperspectral tools across agricultural sectors. Regulatory uncertainty (e.g., drone permissions) further complicates deployment in some regions.

Future Directions (2025–2030)

Looking ahead, the next wave of innovations in hyperspectral plant stress detection will likely involve:

- Lightweight edge computing and optimized algorithms for near‑real‑time inference on UAVs and field devices.

- Hybrid sensor fusion combining hyperspectral, thermal, LiDAR, and fluorescence data to tease apart overlapping stress responses.

- Community‑driven spectral libraries and benchmarking datasets to accelerate model sharing and validation.

- AI interpretability frameworks that provide actionable agronomic insights rather than abstract model outputs.

These emerging directions aim to make hyperspectral imaging both technically robust and practically accessible for plant stress monitoring at scale.

Conclusion

Hyperspectral imaging represents a transformative tool for modern agriculture, bridging the gap between raw spectral data and actionable crop management decisions. By capturing hundreds of narrow, contiguous spectral bands, HSI allows farmers and researchers to detect subtle physiological changes in plants—ranging from water stress and nutrient deficiencies to early disease onset—well before these issues become visible to the naked eye. When combined with AI-driven analytics, machine learning models, and cloud-based platforms like Saiwa’s Sairone, hyperspectral data can be rapidly processed and translated into precise, site-specific interventions, optimizing resource use and reducing yield losses.

While challenges such as data volume, environmental variability, and accessibility remain, ongoing advancements in edge computing, synthetic training datasets, and standardized spectral libraries are steadily improving the practicality and robustness of hyperspectral solutions. Importantly, the integration of multi-platform data—from UAVs and satellites to ground-based systems—enables monitoring at multiple scales, supporting both farm-level decision-making and regional agricultural planning.

Looking ahead, hyperspectral imaging is poised to become a cornerstone of precision and sustainable agriculture, providing a proactive, data-driven approach to plant health management. Its ability to combine scientific rigor with operational usability makes it not just a research tool, but a practical solution that empowers growers, agronomists, and policymakers to make informed, timely decisions that enhance productivity, resilience, and environmental stewardship.

At Saiwa, we are committed to making these advanced capabilities accessible to farmers and agronomists. Through our Sairone platform, users can leverage UAV and satellite hyperspectral imagery, AI-driven analysis, and cloud-based dashboards to detect plant stress early, optimize interventions, and monitor crops at multiple scales. By integrating hyperspectral insights into daily farm management, Saiwa helps translate cutting-edge research into practical, actionable decisions, supporting both sustainable practices and improved yield outcomes.